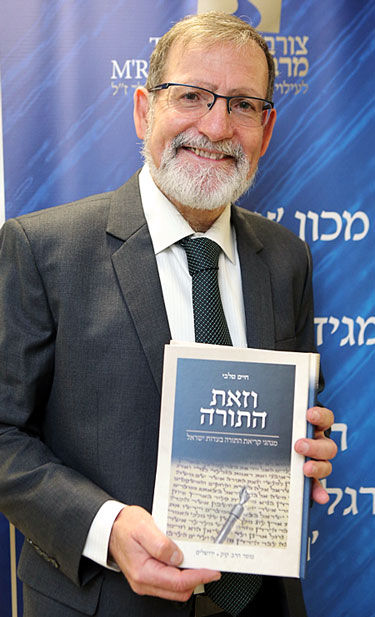

Rabbi Dr. Haim Talbi and his new book

Ever since Ezra the Scribe introduced the regular, public practice of Torah reading (fifth century BCE), Kriat haTorah has been a key component of communal Jewish worship. Following a set procedure dating back some 2000 years to the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, the Torah has been read in synagogues around the globe thrice weekly and on Jewish holidays. Now, in a newly published book, BIU’s Rabbi Dr. Haim Talbi sheds light on Torah-reading customs in Jewish communities in Germany, France, Italy, Yemen, Libya, Tunisia, Morocco, Halab (Aleppo, Syria), Cochin (India), and other places.

Rabbi Dr. Haim Talbi, a BIU alumnus who lectures in BIU’s School of Basic Jewish Studies and also heads a congregation in Rehovot, intertwines historical, literary and social research methods in examining Rabbinic sources (e.g. the Mishna, Talmud, Midrash, Responsa,) in his Hebrew work, ViZot HaTorah — Torah Reading Customs among Jewish Ethnic Groups (Mossad HaRav Kook, 2017). The book — the first of its kind to offer a comprehensive review of Torah-reading customs — evolved from the PhD thesis he wrote more than two decades ago under the guidance of Israel Prize winner in Jewish Studies and BIU Talmudist Prof. Daniel Sperber. “Over the years, I added, expanded and embellished,” he notes.

One of the practices featured in his book is Hagbah — raising the Torah scroll (after each reading) and displaying the text to congregants who often point toward the scroll and recite the verse: “וזאת התורה אשר שם משה לפני בני ישראל, על פי ה’ ביד משה” — “And this is the ‘Torah’ (teaching) which Moses set before the Children of Israel, according to G-d, in Moshe’s hand.” Rabbi Dr. Talbi relays that the first documentation of Hagbah is found in the Tractate Sofrim (Scribes) (14:8), where many of the citations are from the Jerusalem Talmud. The custom of Hagbah spread to many communities, where leading rabbis and poskim referred to it as an “established practice.”

Hagbah in the Italian community: Two men raise the Torah

However, in the late 16th century, Rabbi Raphael Joseph Treves of Ferrara, Italy defended those who refrained from doing Hagbah, out of concern that the Torah would not be properly lifted and might fall. In the 18th century, there were still Italian communities that did not do Hagbah, and in many contemporary Italian communities, the Torah scroll is raised by two men, who each hold a Torah scroll roller (Etz Hayim), in order to safeguard it from falling. Moreover, in order to prevent the parchment from tearing, a special silver rod (Sharvit) is affixed to the rollers when the Torah scroll is raised in order to stabilize it and enable the scroll to be opened.

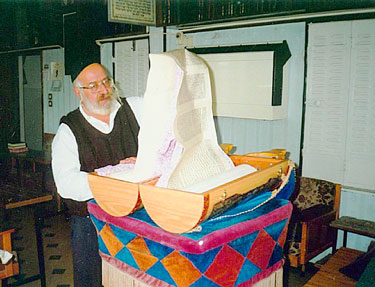

The Yemenite custom of Hagbah

The Yemenite community in Aden similarly did not have the custom to raise the Torah in the usual way due to the concern that the scroll will fall. Just the parchment was lifted but not the encasing — typically an octagonal wooden case. The absence of this halakha in the works of Maimonides, an esteemed authority for Yemenite Jewry, might be another reason why Hagbah was not practiced in certain parts of Yemen.

Rabbi Dr. Talbi relates that he discussed this issue with the late Yemenite Rabbi Yosef Kapach z”l, the foremost contemporary interpreter of Maimonides’ works. “He explained that there is an oral tradition among some Yemenite communities not to raise the Torah scroll at all, in order to reject the deviant practice of the Samaritans who do not follow the Oral Law and only raise the scroll when a high priest is present.”

On the other hand, the Ashkenazic communities in Amsterdam practiced the custom of Hagbah with the stipulation that single men under the age of 25 do not raise the scroll, “probably out of fear that it might fall from their hands,” says Rabbi Dr. Talbi. He relays that to this day in the grand Sephardic Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam the Torah scroll is raised by three or four strong men who were appointed to do so. They are aptly called Levantadores (those who raise up).

In addition to Hagbah, other customs appearing in Rabbi Dr. Talbi’s new book revolve around the “Aliyot” — calling up individuals to recite a blessing over the Torah, special Shabbat celebrations, such as an aufruf for a groom, and the recitation of supplications during Torah reading.